“She’s now wheelchair-bound.” “They’ve been confined to a wheelchair for three years.” When we wheelchair users are spoken of, phrases like these are sometimes used — reflecting the way that some feel about this vital piece of equipment that we rely on. It is seen an instrument of imprisonment, holding us down, keeping us from living full lives. In reality, it is our chairs that give us mobility and independence. While the terms “wheelchair-bound” and “confined to a wheelchair” are both thankfully beginning to be challenged and replaced with ones that focus on independence and personhood, they are still used in news articles regularly as well as in casual conversation.

Examining the genesis of the wheelchair and how far it has come may help change the way that it is perceived; it was not invented as a tool of incarceration, but one of freedom – a truth that is evident in every chapter of its history. The evolution of the wheelchair over the centuries shows that its purpose is to give mobility and autonomy to those who need it most.

Examining the genesis of the wheelchair and how far it has come may help change the way that it is perceived; it was not invented as a tool of incarceration, but one of freedom

Inventing The Wheel(chair)

People who needed help getting around have been getting transportation assistance for much longer than wheelchairs have existed. One might guess that the earliest form of this may have been a simple piggyback ride, or being carried princess-style, or perhaps being pulled on a sled like Bran Stark from Game of Thrones. We may also imagine that wheelbarrows may have been used to move people from one point to another, which might be considered a type of wheelchair.

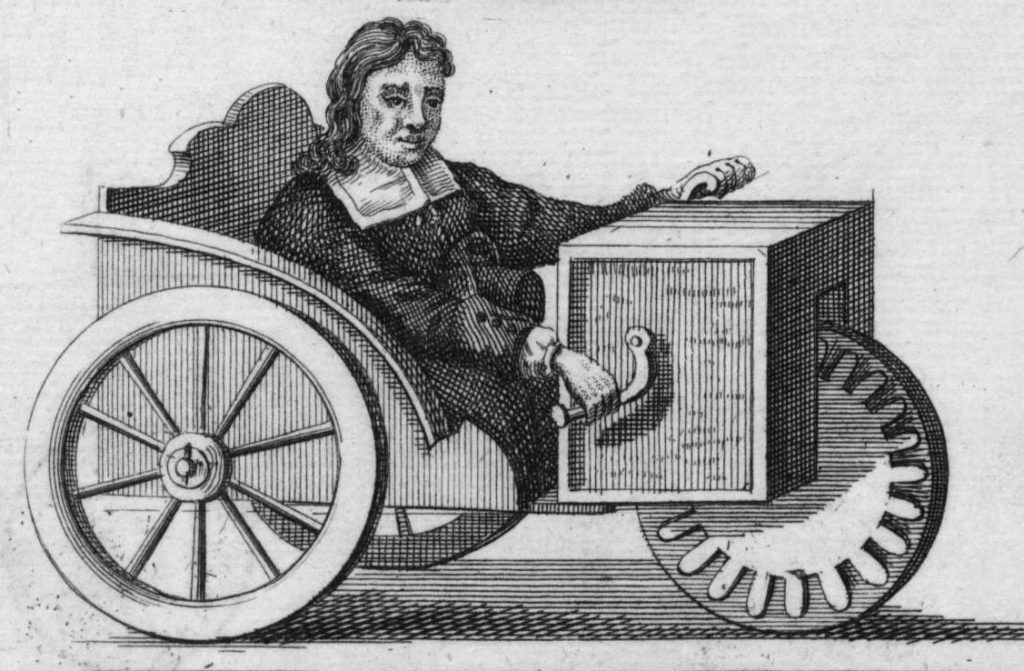

The earliest depiction we have of a contraption that is clearly a wheelchair – or, at the very least, a chair with wheels on it – comes from a collection of Grecian vases and amphorae dated around 440 B.C.(1) It depicts the mythical figure Triptolemus sitting in his mini-chariot-like chair with wheels, and large wings attached to the back of it. Triptolemus was an incredibly important figure in the Greek pantheon; he flew around the world in his wheeled chair spreading the knowledge of how to plant grain and giving the gift of the plow – essentially teaching mankind the concept of modern agriculture. While his seat is technically a wheelchair, there seems to be no mention of Triptolemus using it due to any illness or disability; therefore, using it as a touchstone of “earliest wheelchair” is perhaps a bit of a stretch.

From sixth-century China comes an inscription on a tablet that mentions a wheelchair; from this same period comes a sarcophagus bearing a depiction of a man in a device somewhere between a bed and a chair that rests on wheels.(2) Whether or not this latter object was used by the man in the sarcophagus is unclear.

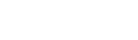

Innovation and use of wheelchairs seemed to pick up significantly in 16th and 17th century Europe – or at least the recordings of such activity did. In 1585, German inventor Balthasar Hacker created a wheelchair(3); in 1595, King Philip of Spain was so affected by gout that a plush chair on wheels was constructed for him to regain some mobility.(4) According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the first recorded invention of a self-propelled wheelchair was in the early 17th century by Johann Hautsch in Nuremberg, Germany.(5) In that same century in 1655 the first recorded inventor of a wheelchair who had a disability himself appears, one Stephen Farfler, a paraplegic watchmaker. He had broken his back as a child, and when only twenty-two years old used his watch-making skills to invent a three-wheeled, self-propelled wheelchair.(6)

In the 18th century along came two men named John Heath and John Dawson of Bath, England. Heath created a chair for “invalids” to use in bath houses – he dubbed the equipment “Bath chairs.” Dawson became the primary producer of these chairs, which had two wheels in back and one in front.(4) These were primarily used by people of means who were ill or disabled. They could be pushed or pulled by others and could even be pulled by horses.(4)

As the years continued, wheelchair designs began to move toward the look of the manual chairs we have today: two large wheels in back and two smaller wheels in front. A U.S. patent in 1869 by A.P. Blunt and Jacob S. Smith is one example of this.(7) It is a sad fact that during and after major military conflicts, usage of disability equipment increases, and the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) was no exception. More advanced medical techniques also meant that injured soldiers would survive at higher rates than in the past. There are several records and photographs from this time that show patients using wheelchairs; some of these chairs are still in existence in both public and private collections.(4)

20th Century Spokes

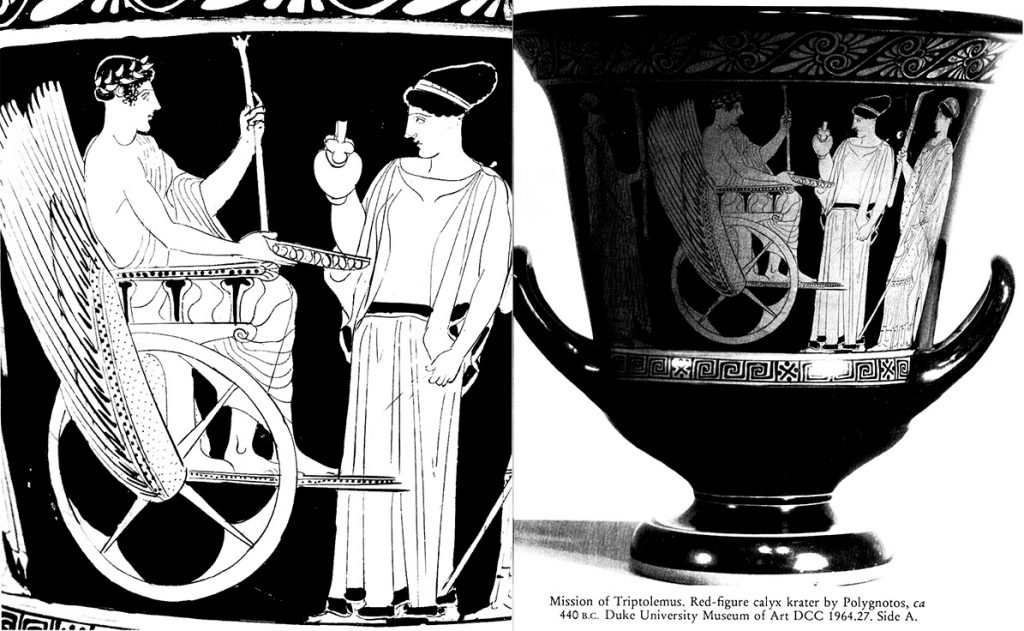

The 20th century saw the creation of several designs and companies that are still serving the disabled population today. A paraplegic man named Herbert Everest and his friend Harold C. Jennings created the first folding wheelchair in 1932.(8) Everest, a mining engineer, and Jennings, a mechanical engineer, designed the chair with an x-frame that allowed it to be folded. It was constructed out of aluminum, which made it lightweight and easy to transport, giving the user more independence. In 1950 the two engineers made a motorized version of the chair using a transistor-based electrical motor. Their chairs cornered the market – too well, in fact. In 1977 the U.S. Dept. of Justice brought an anti-trust suit against the company of Everest and Jennings, accusing them of illegal price-rigging and intimidation of competitors.(9) The case was settled out of court. The company was sold to Graham-Field Health Products in 1996, who continues to make wheelchairs under the Everest and Jennings name.

The first wheelchair-ventilator combination was made in 1962 by British disability advocate Robin Cavendish and Oxford professor Teddy Hall.(10) Cavendish’s name may sound familiar – there was a 2017 movie made about him called Breathe starring Andrew Garfield and Claire Foy which tells the remarkable story of his life and advocacy for ventilator-dependent people.(11) Cavendish tested many equipment prototypes on himself; his efforts continue to provide independence for disabled people to this day.

Another company name that may sound familiar is Permobil (this author happens to have a power assist by Permobil attached to her own chair). Its founder, a Swede named Per Udden, launched it around 1966 after some back and forth with authorities who initially believed that motorized equipment, including electric wheelchairs, should be restricted to roads only.(12) Permobil, still around today, has also acquired other familiar companies such as Tilite and ROHO.(13)

The ultra-lightweight wheelchair was popularize by Quickie, a company founded by Marilyn Hamilton, Jim Okamoto, and Don Helman. After Hamilton was injured in a hang-gliding accident she didn’t want to give up her active lifestyle. Her friends Okamoto and Helman helped design a lightweight wheelchair from the same materials hang-gliders were constructed of; wanting to bring this concept to others with disabilities, the three formed the company Quickie in 1980.(14) Hamilton went on to become a champion wheelchair tennis player as well as silver-medalist skier in the Paralympic games.(15)

If you’ve ever been fortunate enough to enjoy the ocean because of a beach wheelchair – either for rent or provided for free – you have Mike Deming to thank for it. The beach wheelchair was invented by Deming for his wife Karen who was injured in a car accident in 1990, only eight months after they had been married. Driven by the desire to see her continue to enjoy the beach, the prototype was completed in 1994 and the company Debug was born.(16)

It may sound like a thing of the future, but mind-controlled wheelchairs have already been around for over a decade. Mind-control wheelchairs use brain-computer interfaces, or BCIs, to allow the user to use their own brainwaves via EEG to control their chair. There seems to be some debate as to who first invented this type of chair: Diwakar Vaish, Head of Robotics and Research at A-SET Training and Research Institutes in India(17); researchers at the University of Zaragoza in Spain(18); and Toyota and Japanese research foundation RIKEN(19) are a few of those who came out to the press around the same time (2007 – 2009) with this new concept.

Full Speed Ahead

What coming up in the wheelchair technology world, you might ask? Self-driving cars have been around for a few years already; it was only a matter of time before someone started to experiment with self-driving wheelchairs. In 2016, MIT debuted an autonomous mobility scooter, using the same software and sensor configuration they had used in self-driving cars and golf carts.(20) The scooter was able to react to new obstacles presented in its path as it transported a passenger from point A to point B. Creating a successful, fully autonomous wheelchair will prove more of a challenge than a vehicle, however. While vehicles traverse streets and roads that are largely already mapped and can be easily programmed into software, wheelchairs travel on sidewalks, into buildings, and private homes – all places that are largely unmapped.(21) An autonomous wheelchair would need to rely heavily – many times completely – on only its own sensors to gauge the surrounding environment in order to choose the safest path. Self-driving transports do have these sensors; however, at this time navigation has been done primarily by mapping.

Another wheelchair using “smart” technology is Andrew Slorance’s Phoenix i, a manual chair he developed with the help of the Toyota Unlimited Mobility Challenge. Test frames were created via 3-D printing on-site until the chair was perfected, greatly speeding up the development phase. The Phoenix i has a “smart” weight distribution feature that adjusts the chair’s center of gravity as the user moves, reducing risks of falls as well as improving control over varied terrain. Add in automatic braking for inclines and a power assist, and the Phoenix i begins to seem like something out of a sci-fi novel. The chair is still in the development phase, but Slorance and his company, Phoenix Instinct, predict that it will be ready in the next couple of years.(22)

We’ve come a long way from piggyback rides and being carted around in wheelbarrows. Someday soon we wheelchair users may simply push a few buttons to get where we need to go – or no buttons at all, perhaps we’ll just give a thought or mental command. Whatever is coming down the pipeline, it’s important to acknowledge that these inventions will only help if they can get into to the hands of those who need them, which means they either become affordable or are paid for by our healthcare systems. Hopefully those in power will recognize that our wheelchairs are an integral part of us, and act accordingly — because if mobility independence exists for those who need it, then those people deserve to have it.

Sources

- Matheson, Susan B. “The Mission of Triptolemus and the Politics of Athens.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/view/3201/5781

- Slack, Marceline. “History of Wheelchairs.” Wayback Machine. wheelchair-information.com, 2015. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20190307075310/http:/www.wheelchair-information.com/history-of-wheelchairs.html.

- Clareangela. “Leonhard Danner; Designer, Engineer, Inventor.” Leonhard Danner; Designer, Engineer, Inventor. Renaissance Utterances, August 3, 2013. Accessed October 6, 2022. http://renaissanceutterances.blogspot.com/2013/08/leonhard-danner-designer-engineer.html

- Slawson, Mavis C. “Wheelchairs through the Ages.” National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Surgeon’s Call, July 19th, 2019. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/wheelchairs/

- Watson, Nick. “History of the Wheelchair.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-the-wheelchair-1971423

- Bonneau, Claire. “History of Wheelchairs: Complete Timeline & Their Revolution.” Loaids, April 7, 2022. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://loaids.com/history-of-wheelchairs/

- Blunt, A.P., and Jacob S. Smith. Patent for Improved Invalid-Chair, issued February 16, 1869.

- books, Floss. “Who Invented the Wheelchair?” Mental Floss. Mental Floss, February 2, 2009. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/20768/who-invented-wheelchair

- Anderson, Jack, and Les Whitten. “Jack Anderson Column on Antitrust Suit against Everest & Jennings (1977).” Newspapers.com. The Daily Standard, December 26, 1977. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/3116361/jack-anderson-column-on-antitrust-suit/

- Renton Alice, Tim. “Obituary: Robin Cavendish.” The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, August 10, 1994. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-robin-cavendish-1382697.html

- Barraclough, Leo. “Andrew Garfield, Claire Foy Join Andy Serkis’ ‘Breathe’.” Variety. Variety, May 5, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://variety.com/2016/film/global/andrew-garfield-claire-foy-andy-serkis-breathe-1201767235/

- “Per Uddén.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, October 19, 2022. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Per_Udd%C3%A9n

- Permobil’s history. Permobil. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.permobil.com/en-us/this-is-permobil/our-history

- “Marilyn Hamilton: Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History |.” Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers | Marilyn Hamilton | Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History |. Smithsonian. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://amhistory.si.edu/sports/exhibit/removers/wheelchair/index.cfm

- “Sci Superstar: Marilyn Hamilton.” SPINALpedia, March 8, 2022. https://spinalpedia.com/sci-superstar-marilyn-hamilton/

- Deming, Mike, and Karen Deming. “Our Story – Debug Beach Wheelchairs.” DeBug Beach Wheelchairs and Mobility Products. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.beachwheelchair.com/about-debug

- Bhalla, Nikita. “No Buttons, No Joystick; Please Welcome the World’s First Mind-Controlled Wheelchair.” India Today. India Today, March 17, 2016. https://www.indiatoday.in/lifestyle/wellness/story/no-buttons-no-joystick-please-welcome-the-worlds-first-mind-controlled-wheelchair-created-by-diwakar-vaish-313689-2016-03-17

- Cole, Emmet. “A Wheelchair That Reads Your Mind.” Wired. Conde Nast, January 29, 2007. https://www.wired.com/2007/01/a-wheelchair-that-reads-your-mind/

- “Toyota Makes a Wheelchair Steered by Brain Waves.” New Atlas, May 2, 2015. https://newatlas.com/toyota-wheelchair-powered-brain-waves/12121/

- Hardesty, Larry. “Driverless-Vehicle Options Now Include Scooters.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 7, 2016. https://news.mit.edu/2016/driverless-scooters-1107

- Braze Mobility. “What Are Autonomous Wheelchairs?” Braze Mobility. Braze Mobility, Inc., January 15, 2020. https://brazemobility.com/what-are-autonomous-wheelchairs/

- “Medical 3D Printing Reinvents the Wheelchair – and Orthosis.” BigRep Industrial 3D Printers, March 19, 2021. https://bigrep.com/posts/medical-3d-printing-prosthetics/